Translated by Margaret Sayers Peden

'And of Clay Are We Created' is a short story by Chilean-American author, Isabel Allende, which appears in her 1989 collection The Stories of Eva Luna. It is based on the true story of Omayra Sanchez, who was a young victim of an earthquake in Colombia in 1985. 'What's in a Name?' 'What's Your Mud?' Azucena- Spanish for 'Lily,' her first communion name. Resurrection The resurrection of Jesus is the Christian belief that Jesus Christ miraculously returned to life on the Sunday following the Friday on which he was executed by crucifixion. Start studying 'And of Clay are We Created' by Isabel Allende (1942-). Learn vocabulary, terms, and more with flashcards, games, and other study tools. AND OF CLAY ARE WE CREATED by Isabel Allende, 1994 Because of space limitations 24 of Isabel Allende 's stories, including 'And of Clay Are We Created' 'De barro estanos hechos'), that were originally intended for inclusion in Eva Luna were later published separately in The Stories of Eva Luna (Cuentos de Eva Luna). Isabel Allende isael aende born August 2 1942 is a ChileanAmerican writer Allende whose works sometimes contain aspects of the magic realist tr.

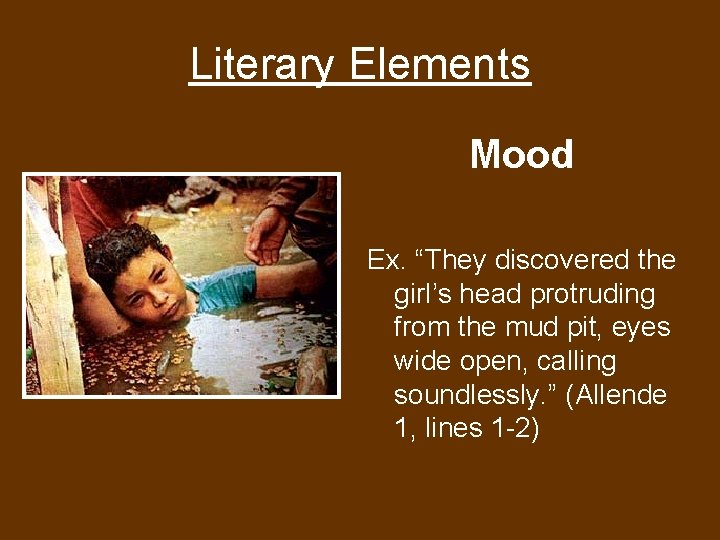

They discovered the girl’s head protruding from the mudpit, eyes wide open, calling soundlessly. She had a First Communion name, Azucena. Lily. (…)

Source: Allende, Isabel “And of Clay Are We Created.” In: Isabel Allende The Stories of Eva Luna. Translated by Margaret Sayers Peden 1991.

Available at [🔗].

This story was inspired by Frank Fournier’s picture of Omara Sanchez who was a victim of the 1985 Armero tragedy in Colombia. [🔗] More recently, Nilüfer Demir’s picture of Alan Kurdi (2015), showing the lifeless body of a Syrian toddler washed ashore in Turkey, shocked the world and made a change to refugee politics. It is one of the Time 100 Photos series and Brendan O’Neill, in The Spectator article “Sharing a photo of a dead Syrian child isn’t compassionate, it is narcissistic” is critical of how the picture was shared on social media.

Nilüfer Demir “Alan Kurdi” Time 100 Photos. [🔗]

Brendan O’Neill “Sharing a photo of a dead Syrian child isn’t compassionate, it is narcissistic.” The Spectator,3 September 2015. [🔗] and [🔗]

1. Rolf Carlé decides to forego his professional duties, that is to put down the camera, and decides to provide companionship to the dying girl. What is driving him?

2. How does Rolf Carlé’s experience in reporting on the tragedy affect him personally? Do you think that it makes a positive change in his own life?

3. Who is the narrator? What is her perspective on Rolf Carlé’s predicament?

4. If you were on the editorial team of a newspaper, would you argue for or against publishing Nilüfer Demir’s picture of Alan Kurdi? What speaks for publishing it? What speaks against?

'And of Clay We Are Created, ' compiled by Isabel Allende, explores what social psychologists refer to as the bystander effect. In the story, Azucena is a little girl who is trapped in the mud, and needs help if she is to survive. While the girl suffers and was filmed by countless reporters, no person actually comes to save her. The reporters tend to be more worried about filming the girl than with saving her life. 'The bystander effect is a psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to lend assistance within an emergency situation when other humans can be found than when they are alone' (Myers, 463). Throughout the story, Allende uses voyeurism as a crucial dramatic device as she connects Eva Luna to Rolf and Azucena. With the interactions between your characters, Allende can investigate how voyeurism can lead to social apathy and act as a desensitizer in a crisis.

Allende's 'And of Clay We Are Created' describes what sort of host of reporters and cameramen become desensitized and apathetic towards Azucena as she actually is dying a preventable death. The situation obviously characterizes the bystander effect. Tests by John Darley, a social psychologist at Princeton University, Allan I. Teger, and Lawrence D. Lewis, his colleagues, demonstrated this psychological phenomenon in the laboratory. The most frequent explanation of the phenomenon is that, the more people present, the much more likely the average person observer will pass off the duty to help the victim, regrettably believing that there is bound to be somebody who is helping already or will help soon (Darley, Lewis, and Teger 395). As more reporters arrive on the scene, each individual reporter feels less obliged to really, help the girl. Although in the storyplot Allende does mention, 'Soldiers and volunteers had arrived to rescue the living, ' the reader is made aware that a lot of the rescue effort is ineffective and cumbersome (47).

In this way, Allende poignantly criticizes the government for not responding appropriately, when she highlights 'geologists had set up their seismographs weeks before and knew that the mountain had awakened again' (47). She continues on to say that the geologists had 'predicted that heat of the eruption could detach the eternal ice from the slopes of the volcano, but nobody heeded their warnings' (Allende 47). The immediate thought that strikes the reader is that this completely ghastly episode could have been thwarted entirely only if the villagers have been either directly forewarned or even forced to relocate by the authorities. Interestingly, Allende appears to point out that the villagers themselves didn't heed the warnings of the geologists, perhaps to mitigate any blame on the federal government and the media.

Adding to the frustration and ignorance, the leaders of the federal government and military are unable and/or unwilling to help secure a pump that could have drained the mud water, which could have effectively saved the tiny girl's life. Though it is granted that Azucena is not really the only person in dire need of rescuing, the fact that she 'became the symbol of the tragedy' (47) while never receiving help is actually heartbreaking. Instead, the complete world must watch the girl die a slow, agonizing death in front of the cameras. Why is the situation so horrifying is that event closely parallels a genuine incident that occurred in Columbia in 1985 ('Picture power'). A volcano had erupted (just as the story), and vomited debris and catalyzed mudslides that engulfed the towns nearby the mountain. A photojournalist who proceeded to take her photograph, which made headlines throughout the world, found a 13-year-old girl. Many who saw the photographs were appalled how 'technology have been in a position to capture her image forever and transmit it around the world, but was unable to save her life' (Picture power'). Actually, Allende seems to explicitly question the integrity and value of human technology as she describes how 'more tv set and movie teams arrived with spools of cable, tapes, film, videos, precision lenses, recorders, sounds consoles, lights, reflecting screens, auxiliary motors, cartons of supplies, electricians, sound technicians, and cameramen, ' yet how these were unable to secure one life-saving pump (50). It is almost unbelievable how a lot advanced technology and machines are taken to film the disaster instead of the amount of materials and supplies that are needed to assist in saving the victims of the calamity. Allende is nearly begging someone to help the lady as Rolf keeps pleading for a pump (50).

Allende also masterfully foreshadows that the try to save Azucena's life will inevitably fail as she tells how 'anyone wanting to reach her was at risk of sinking [themselves]' (48). Whenever a rope is thrown to the girl, she tries to seize the rope, but ends up sinking deeper in to the mud (Allende, 48). At this point, the reader must ask whether Azucena actually wants to be saved. She must have experienced the mud for quite a while now, and the pain and shock could have been eating away at her will to survive. Actually, when the rope is thrown at her, she makes no effort to catch the rope (Allende, 48). Has Allende doomed Azucena to death already? For some time, the reader is given little rays of hope that the girl will eventually be rescued and this there will be a happy ending, but in all honesty, most of the signs point toward certain death for the girl. Another try to rescue her by tying a rope beneath her arms is also thwarted when the girl cries out in pain from them pulling on the rope (Allende, 48). She actually is stuck in the mud and is merely kept from being totally consumed by the mud when she is given a tire as a life buoy (Allende, 48).

Allende skillfully blends fact and fiction, by creating her own stories from events that contain transpired in real life. She creates characters that tell a gripping story, and be very believable. In the story, Rolf is a reporter who finds Azucena, the girl trapped in the mud and debris. Samuel Amago, a literary critic writing in the Latin American Literary Review, asserts that '[Rolf] tries to give [Azucena] the inspiration to live on while the impersonal television set cameras look on without helping' (54). He is becoming battle-tested through his work as Allende explains: For a long time, he previously been a familiar figure in newscasts, reporting live at the scene of battles and catastrophes with awesome tenacity. Nothing could stop himit seemed as if nothing could shake his fortitude or deter his curiosity. Fear seemed to never touch him, although he had not been a courageous man, far from it. (47)

Through Azucena's struggle, he eventually ends up undergoing an individual transformation by abandoning his aloof stance as a reporter that had served him so well in previous episodes, and by passionately embracing the girl's fate personally.

This is where voyeurism comes into play. This isn't the type of voyeurism confined and then the sexual fetish of receiving gratification from observing a sexual occurrence or object, but as Elizabeth Gough, a literary critic writing in the Journal of Modern Literature, states that it also includes any kind of 'intense, hidden or distant gazing' (93). Eva Luna is not physically present with Rolf and Azucena, but she is able to see everything that is occurring through the news headlines. She is in ways, spying on the two people. The intensity of her gazing is noticeable as the reader finds that Eva is emotionally, linked as she witnesses the events on television.

The first aspect of voyeurism we find is the camera in the storyline. Rolf is a reporter and sees everything by using a lens. Allende describes how 'the lens of the camera had a strange effect on him; it was as though it transported him to another time from which he could watch events without actually participating in them' (47-48). The mechanical tailoring of the cameras rolling as a human life is slowly failing portrays the media as impersonal, cold, and heartless. To Rolf, the camera lens acted such as a desensitizer and promoted a sense of separation between Rolf and his surroundings so that while he was physicallyat the scene, his mind is at another safe, secure place. Eva Luna realizes that for Rolf, the 'fictive distance [between the lens and the true world] appeared to protect him from his own emotions' (321). Rolf had erected a psychological self-defense mechanism in response to his traumatic experience as a young child. His trauma mostly stems from his guilt for not protecting his sister, Katharina, of their abusive father. Allende shows that Rolf could not forgive himself for not saving his sister, but through his efforts to save Azucena- and through his subsequent emotional revelations- he could finally 'weep on her behalf death and for the guilt of experiencing abandoned her' (328). Through this act of acceptance, Rolf finally realizes that all his life he had been 'taking refuge behind a lens to check whether reality was more tolerable from that perspective' (Allende 328). Allende suggests that Rolf's voyeuristic approach to life had led to shallow success as a reporter, and weakened his ability to trust his own thoughts and also other humans. Why else did it take him such a long time to simply accept that Azucena was going to die? It was because he was too afraid to feel the pain of loss again, exactly like when he lost his sister.

One of the most memorable turning points in the story occurs when Azucena helps Rolf breakdown his emotional barriers and to come to conditions with own past. Azucena accomplishes this not by saying much, but by hearing Rolf's stories until he could not hold back the 'unyielding floodgates that had contained Rolf Carle's past' (Allende, 327). In a very classic reversal of roles, Azucena takes on the nurturing role of the adult during Rolf's weak and vulnerable moments. Allende portrays Rolf's mother as an uncaring, frigid woman who not give him emotional support or to dry his tears (329). Azucena is the one who tells Rolf never to cry, something a normal mother figure could have done (Allende 329).

Voyeurism is also evident when Eva Luna, Rolf's lover, watches all that occurs in the news on television. The physical distance between Eva and Rolf is palpable, as Allende explains through Eva: 'Many miles away, I watched Rolf Carle and the girl on a tv set screen' (324). Nonetheless, through the storyline we are made aware that Eva and Rolf are intangibly bound together. The reader is left in the similar plight of Eva; we see natural disasters and tragedy through the eyes of the media. Therefore, in a sense, the media helps desensitize humans to real tragedies that occur by providing a fictive, safe distance because of its viewers. This is precisely the reason actually experiencing something can leave a lasting impression whereas seeing something on television set can seem obscure and impartial.

However, in the storyplot, this fictive distance actually fuels the reality of what's happening at the disaster scene to Eva. For Eva, it is really as if she actually is physically present at the disaster with Rolf and Azucena. The images on the television help her visualize what Rolf is seeing and even thinking at each precise moment, 'hour by hour' (Allende 326). It is indeed surprising and amazing how Allende portrays the attachment of Eva to Rolf even though Eva is bound to the impersonal medium of television to 'keep in touch' with her lover. Allende explains that Eva was 'near [Rolf's] world and [she] could at least get a feeling of what he lived through' (324). She further clarifies that while '[t]he screen reduced the disaster to an individual plane and accentuated the tremendous distance that separated [Eva] from Rolf Carle; nonetheless, [she] was there with him' (324). Eva and Rolf were connected at heart as well, as Eva could overhear the verbal exchanges between Rolf and Azucena to the point where she was present with them (Allende 326). Although it can be argued that Eva is much more personally linked and involved than the general reader is to the problem at the site of the catastrophe, the reader is drawn in to the conflict and struggle by the personal narrative of Eva. The reader is told the storyline through Eva's perspective, and therefore our company is left with the feeling that is related to the storyteller. The voyeurism goes many ways.

Compounding this idea of long-distance interconnectedness is how Allende ties Eva to Azucena, in addition to Rolf. Through Rolf's interplay with Azucena, Eva is hurt by the girl's every suffering, and feels Rolf's frustration and impotence (Allende 324). The three are enjoined together in a peculiar love triangle. Rolf tells Azucena that he loves her 'more than he loved his mother, more than his sister, more than all the ladies who had slept in his arms, more than he loved [Eva], his life companion' (Allende 330). Certainly, he does not mean Eros love, the type between adult women and men, but a far more intrinsically human one of neighborly love and goodwill. Eva, in her turn, expresses her love for Rolf and Azucena when she admits that she 'could have given anything to be trapped for the reason that well in her place, [and] would have exchanged her life for Azucena's' (Allende 330). Our company is then forced to analyze whether the voyeuristic qualities of the media affects the several types of l

ove shown in the storyline. Generally, the media helps Eva to express more powerful love for Rolf also to become linked to Azucena, whom she had never met. Without the media, Eva could not have known what had happened at the disaster as well as the identity of the tiny girl who had tremendously afflicted Rolf. For Rolf, his initial voyeurism through the lens of the camera had acted as a desensitizer and emotional barricade, so when confronted with the crisis, his love for Azucena is bolstered as he comes to realize he must forget about his past and obligingly accept the situation. However, Rolf's love for Eva appears to have taken popular after he returns from his ordeal (Allende 331).

And Of Clay Are We Created By Isabel Allende

A bitter question is forced to ask is what or who exactly Allende is blaming in her story, or if she actually is even blaming someone or something in particular for Azucena's death. Although it is clear that Rolf definitely undergoes a psychological metamorphosis, we cannot logically assume that this change is designed for the better. The end of the story suggests that Rolf won't be the 'same man' again, but that he'll eventually 'heal' (Allende 331). Eva hopes that one day when Rolf 'return[s] from [his] nightmares, ' they shall be the happy couple they used to be (Allende 331). However, the ending shows that for Rolf, the incident was as traumatic as his initial trauma as a child. Rolf is not free from his past, as Eva would like him to be. Actually, although he is free of his childhood trauma, he is still haunted by his failure to save lots of Azucena. Perhaps Allende is suggesting that emotional healing can only just occur when the victim is ready to be healed.

And Of Clay Are We Created By Isabel Allende

Then is Allende blaming the media for Azucena's death? Alternatively, is she pointing out the gross inability of the federal government to intervene swiftly and also to protect its citizens? Probably, a little of both. The media is plainly depicted in a heartless, cold manner. Why did anyone not helped? Nevertheless, if anybody thing is usually to be blamed, it ought to be the society where this incident occurred. Allende appears to be challenging the ineptitude and unpreparedness of the federal government and its leaders for not mustering the resources and courage to save lots of the girl. The villagers are also criticized as unheeding fools who only brought the calamity upon themselves by not hearing the geologists. This makes it hard at fault anyone by any means. Perhaps Allende is suggesting that it is unnecessary to blame anyone, but rather to calmly accept what happened, as Azucena does in the long run. One thing is though: that Allende does not approve of the social apathy that permeates throughout the storyline, and claims that it was the unwillingness to help that eventually kills Azucena. This makes us wonder, precisely how dangerous it can be to stay a bystander, rather than actively assisting those who need our help.